Values development in education

Paving the way to a values-based education

The Centre for Ethics of the University of Tartu explores the topic of ethics and values both as a part of research and teaching activities and as a part of the wider aim to contribute to the development of the Estonian society as it reflects upon the theme of ethics and values. In 2009, the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research approved the national programme “Values Development in Estonian Society 2009–2013”. The programme has been subsequently renewed twice, currently for the years 2021–2026.

Many schools in Estonia consciously focus on the issues related to values, and due to the activities of the national programme, their number has noticeably increased over the recent years. Centre for Ethics has supported schools in 74 local municipalities out of 79 with various measures on values-development. The ultimate aim of the programme is to widen this circle of motivated institutions so that all educational institutions in Estonia would recognize that focusing on values education and values development enables them to achieve their aims better.

In motivating teachers, educational administrators and other decision makers, the Centre for Ethics considers it important to support their reflection upon the aims of education. In the following chapters Centre for Ethics' wide experience with values-based education is described and provided with useful resources.

Prof. Margit Sutrop, Head of the Centre for Ethics of the University of Tartu

The societal context and need for a values development programme on the state level

Estonia reclaimed its place among democratic countries in 1991 after the Soviet occupation that had lasted half a century. Political and economic reforms were carried out over a very short period but unfortunately, changes in the society’s values system were not made as rapidly. In the words of Lennart Meri, the President of Estonia at the time: “We have succeeded in everything apart from recreating the Estonian values system. Next to human losses, moral losses hurt the most. These linger on in our post-soviet manners and undermine our work ethics, values, and honesty.”[1] Many moral values (honesty, consideration, dignity) and social values (democracy, justice, tolerance, responsibility) had been devalued or become void of content during the time of Soviet occupation.

According to sociological studies, Estonian society of the mid-2000s was characterised by a low level of trust, lack of cohesion, disregard for health and the environment, alienation from the state, a low level of citizen activity, the prevalence of an individualistic mentality, and the succumbing of moral principles to hedonistic and pragmatic principles. The World Values Survey[2] that analyses people’s value judgments and changes in them across more than 80 countries defined Estonia’s position on the world values map through two aspects: similarly to other countries of protestant Europe and Confucian countries, Estonia favours secular-rational values (individual freedom and independence); at the same time, like other Eastern European countries, it prefers survival values over self-expression values (low level of support for tolerating differences, civil liberties, and freedom of expression). This depiction of Estonian values did not please anyone and it started a broad discussion in our society about who we were and who we wanted to become 15 years after the restoration of independence.[3]

This is how the Ministry of Education and Research got the idea to create a state values development programme that would support the nurture and development of values in the Estonian society. Nearly five years were spent arguing over the need for the programme and its content. In 2008, the Ministry of Education and Research commissioned our Centre for Ethics at Tartu University to compile the values development programme, tasking us to find a solution that satisfied all parties. At first, the public regarded the idea of a values development programme with caution: while some feared that people would be forced to accept certain values, others were critical of the programme for not promoting certain values (e.g., Christian) over others. In the end, it was agreed on that the objective of the values development programme would not be to shape specific values but rather make people think about their values and develop skills for discussing them and justifying choices made on their basis. In addition, the aim was to create a forum for discussing values and agreeing on which values could be held in common.

The values development programme received thorough preparation: the Centre for Ethics conducted media monitoring, interviewed civil society organisations, and organised an essay contest In Which Estonia Do I Want To Live? with the President’s Academic Advisory Board. The patron of the contest was Toomas Hendrik Ilves, the President of Estonia. 326 essays were submitted to the president’s contest with the authors’ age ranging from seven to 94.[4] The essays, opinion pieces and answers on the civil society organisations’ survey form all stated that Estonia was dominated by obsession with success and pragmatism and that there was a lack of tolerance, consideration, and preparedness to assume responsibility. Many of those who responded found education to be the tipping point in the development of the society.

Thus, education became the focal point of the state programme Values Development in the Estonian Society that was approved in 2009. Since a person’s values largely develop in childhood and youth, we decided to place emphasis on values education in the framework of educational institutions. The compilers of the programme found that preschools and schools are the place for systematic values education. Since home and the media also play an important role in developing the values of young people, the whole society must critically contemplate what kind of an example we are providing and in what kind of environment young people’s values are being shaped.

We were aware that we cannot hope for rapid changes. Our reasoning was, if we want there to be changes tomorrow, we must put all our efforts into educating young people today. This meant re-evaluating educational objectives, updating curricula, training teachers, developing methodologies and providing materials to teachers on values education.

An important choice for Estonian society – transitioning to values-based education

Initiating the activities of the values development programme in 2009 also gave us the incentive to re-evaluate educational objectives. We found that previously the main objective of education had been to ensure economic growth, but this view was too narrow. Education’s much broader objective should be to create conditions for a happy life and societal and cultural cohesion. We found that if we did not think about what a person needed to be happy and merely focused on what they needed to know, we were treating that person like an object or a vessel that we were trying to fill with all the world’s knowledge. This results in overburdened school curricula where the knowledge gained is not associated with real life, and where students are expected merely to obey quietly and learn things by heart. Thus, students find little joy in going to school, becoming stressed and tired. Teachers who are burdened by curricula overly filled with facts, lack of interest from students or even lack of skills to give lessons in an inclusive and interesting manner also become unhappy and exhausted.

It was initially difficult to make the public and policy makers understand the gravity of the situation, since international assessments such as TIMMS, PISA, etc. indicated that the level of knowledge of Estonian students was good. They refused to see the other side of the coin: that in addition to good results, the studies also showed that our students lacked the skills for recognising scientific problems and utilising scientific evidence. Compared to the OECD average, Estonian students showed little interest in natural sciences or a desire to work in related fields. Studies also showed that the level of students who liked school was low in Estonia and that there were many problems with school violence.

We pointed out that the problems revealed in these studies could be solved by recognising, acknowledging, and promoting the values education function of schools. We showed that the Estonian school is faced with a challenge of becoming a values-based school where school culture helps young people to become creative well-rounded persons who can fully apply themselves in all of life’s main areas: at work, in family life, and in society. We strove to integrate the idea of a school that prepares people for a happy life and self-fulfilment into the main part of the new national curricula for basic and upper secondary schools. The new curricula now indicate that a school must help students fulfill their interests, inclinations and abilities and ensure the development of core values.

We concluded that one of the greatest challenges in Estonian schools is transitioning from a cramming-based school to a values-based school characterised by learning that is focused on development and cooperation. In a values-based school, teaching not only means communicating knowledge but also supporting the development of individuals. Values are of equal importance to skills and knowledge. In addition to learning content, emphasis is also placed on values education that aims to stimulate values which form the basis for the synergy between living a happy life and creating a cohesive society. In order for values education in schools to be effective, we need a supportive school culture, shaped by values development.

Values development is a complex process which involves the entirety of school life and includes setting conscious goals and formulating common values expressing them in the school environment, communication and learning processes, appropriate learning methods, grading and constant reflection upon values. A values-based school views the student as a partner whose abilities and character are developed in cooperation with teachers, support specialists, and parents. A values-based school is a place where happy students learn, and happy teachers teach because there are good relationships and a school culture that supports cooperation.

Values in national curricula

Discussions on values-based education led to laying down the core values in the national curricula for basic and high schools that were approved in 2011. Values and morality are a recurring topic and the importance of developing the students’ value competencies is emphasised.

The core values in the basic and high school curricula are the same. The following are considered core values:

- human values (honesty, consideration for others, respect for life, justice, dignity, respect for self and others);

- social values (freedom, democracy, respect for the native tongue and culture, patriotism, cultural diversity, tolerance, environmental sustainability, lawfulness, solidarity, responsibility, and gender equality).

Both basic schools and high schools are tasked with educating children formally as well as informally. Their objectives are formulated somewhat differently, indicating the role of the school as value educator on different levels. According to the national curriculum, basic schools “contribute to students growing up to be creative, diverse individuals who can fully apply themselves in various roles: in family circles, at work, and in public.”[5] According to the national curriculum for high schools, the task of a high school is to “prepare young people to function as creative, diverse, socially mature, reliable individuals who acknowledge their goals and can achieve them in various areas of life: as partners in personal life, as bearers and promoters of their culture, in various positions and roles in the labour market, and as citizens who are responsible for the sustainability of their society and natural environment.”[6]

Basic schools are tasked with helping each student find their strengths, weaknesses, and talents by guiding them towards fields they are good at and interested in and helping them overcome their weaknesses. In doing so, it is important that young people who have good manual skills and favour practical activities are helped to form a positive attitude towards vocational education. This attitude also needs to be supported by families and society. High schools continue the values education that began in basic school, primarily shaping values and judgements that form the basis for a synergy between living a happy life and creating a cohesive society. Education at the secondary level supports the development of autonomous individuals who are self-aware, make reasoned choices, and can set and achieve their goals.

Moving towards a concept of learning that is centred around development and cooperation

Updating the curricula of general education institutions was supported by the process of preparing the Estonian lifelong learning strategy (2014–20207)[7] that took place in parallel. Both the general education school curricula and education strategy were based on the realisation that education shapes and carries values which form the basis for personal happiness, cultural sustainability, and social collaboration, thus supporting the development of the state’s economy by developing its human resource. The Estonian lifelong learning strategy was an initiative of three parties – the Estonian Cooperation Assembly, the Estonian Education Forum, and the Ministry of Education and Research. All the parties agreed that the objectives of education require a wider interpretation in order to update Estonian education. The challenge of the education strategy became laying down broader objectives for education. This task was entrusted to Marju Lauristin, Professor of Social Communication at the University of Tartu, and the undersigned. In the source document of the strategy, we gave reasons why education holds a personal, cultural, and societal value:

“The personal value of education: Education helps to discover and nurture a person’s abilities, support ongoing self-analysis, and the setting of goals throughout their life. Through education, members of society can develop into self-aware individuals who are able to learn. They become active subjects who want and know how to make their dreams come true by applying all their abilities and talents. Education supports people in forming their identity and increasing their quality of life so that they can deal with personal and social challenges in a dignified and caring manner. /…/

The cultural value of education: Systems of signs (languages) created in a culture, beliefs and values preserved by using them, models of acting and behaviour, and skills of creating, reading, and interpreting cultural texts are passed on through education from one generation to the next. Creative use of these skills supports the constant development of common meanings in a culture, helping to preserve both popular culture and the inner cohesion of minority cultures.

Education is the most important mechanism of cultural sustainability, as it allows the new generations and members of a society to shape their identity and relate to the past, present and future. The skills of translating and interpreting texts, signs and meanings from other cultures obtained through education form the basis of inter-cultural dialogues and the valuation of cultural diversity without which Estonia could not take part in the European and global cultural sphere.

The value of education for the development of society: Education is a source of intellectual and social capital necessary for the existence and development of society. Education supports social cohesion, increasing its flexibility, reflexivity, creativity, and capacity for innovation. More specifically, education helps to support a society’s ability to create and apply new technological means for economic development and people’s increased well-being. The future success of the Estonian society is dependent on its ability to cope and act creatively (including proactively) in the rapidly and unexpectedly changing conditions of the global, technological, economic, and ecological environment. Lifelong learning that supports this ability creates the preconditions for economic development based on knowledge and innovation in Estonia.”[8]

The challenges of the lifelong learning system in Estonia for the next decade were laid down based on the personal, cultural, and societal values of education from which the strategy originated.

From the aspect of its personal value, the greatest challenge of education is personalising the learning process based on the need for comprehensive development of each learner’s character and their fundamental right to high-quality education. The challenges of education’s cultural role are amplified by the international openness and multicultural nature of Estonia’s society on the one hand, and on the other, by globalisation and a network-based society. The need to stimulate the Estonian society challenges education: to prepare people for taking on a more active role as citizens and successfully finding self-fulfilment in an innovation- and knowledge-based society.

In the course of discussing the strategy we concluded that the primary challenge of Estonian education was to move towards a concept of learning that is centred around development and cooperation which should increase the motivation and satisfaction of teachers and minimise failure at school. Since the Centre for Ethics was leading the working group that was focused on changing the concept of learning, I can also convey the discussions that took place. We found that if we wanted to see creative, enterprising persons who think critically, who can take care of themselves and have skills for communication and cooperation, we had to account for the development and support of these characteristics in the selection of methods used in the learning process. Sparking interest and preserving the curiosity of learners are the key factors in a successful learning process. It is important to support the individual and social development of each learner and stimulate their creativity and individuality, which means rethinking the roles of teacher and learner and placing value on cooperation on all levels.

In implementing a concept of learning based on development and cooperation, teachers/instructors need to become more than authoritarian communicators of knowledge. Rather, they need provide guidance and support, enabling students to assume responsibility for directing their own learning process and helping them to develop their personal abilities. Differences in learners need to be acknowledged, including valuing different types of talent (artistic, practical, social, emotional-emphatic) and ways of thinking (e.g. imaginative thinking). In addition to the learning content, value should be placed on developing social skills, including communication and cooperation, the ability to observe one’s own actions and see their consequences, set goals, create and preserve friendships, evaluate aspects that influence good and bad luck, overcome despair and dejection.

Naturally, rethinking the role of the teacher meant changing the role of the student. We emphasised that students must become subjects instead of objects, having more autonomy and right to self-determination, but also more responsibility. We wrote that learners would be put at the centre of the learning process as the source for acknowledgement, decisions, and activities. Students and teachers must become partners whose cooperation is based on mutual trust.

Teachers as supporters of students’ development

It is easy to say that the roles of teachers and students must be changed and that there is a need for more cooperation and a personalised approach. But nothing changes if we do not know how to do it, or if we lack motivation to change anything at all. A strategy could only say what we should do. We dealt with the how aspect of it in the course of the numerous seminars, conferences and trainings that took place in the framework of the values development programme. In several discussions, students expressed concerns that teachers did not show respect towards them. Teachers were surprised by this and did not understand what the students expected of them. I remember when we talked about this at the conference The Student – e Object or Subject of Values Education? that took place in December 2009 and many educators did not understand the problem. They were doing everything for their students, did this not make them subjects? At the same time, some teachers complained that they could not regard students as partners because there was an invisible wall between them.

We familiarised ourselves with the best practices through competitions organised in schools and preschools and found many contributors among teachers, support specialists, heads of schools, and officials from the Ministry of Education and Research. The main target group of the values development programme became teachers as key persons in values education that shaped students’ attitudes toward values (creativity, enterprising spirit, tolerance, honesty, consideration for others, etc.). During the trainings we emphasised in the trainings that every teacher is a values educator, whether or not they want to be. At first, we faced opposition in this regard – there were many teachers who said that they were only teaching their subject (maths, foreign language, or natural sciences) but did not want to give guidance. We had to show them that teachers always guide children by means of their example, their attitude towards students, and how they teach or communicate with them. Therefore, teachers must choose whether to acknowledge their role as a value educator or continue to do it unconsciously. As value educators all teachers should begin by clarifying their own values. Unfortunately, it was revealed that many teachers were not used to analysing their actions and the values underlying them. They were often unaware which values they were communicating by different ways of acting.

Halliki Harro-Loit, Professor of Journalism at the University of Tartu, came to our aid and used practical examples gathered from schools to show participants in schools where and how they were expressing values in their activities. It was illuminating for both teachers and trainers to see how (first-hand and recorded) observations of lessons and recesses, rituals and school events (ceremonies, class events) or analysis of meeting minutes and letters can enable understand whether everyday activities are actually based on the agreed-on values or whether, instead, there is a large gap between the declared and lived values. We found schools and preschools that were ready to illustrate the functioning of values communication based on the example of their school culture.

We also found out how teachers are currently being prepared to handle value education. We analysed the curricula of two institutions of higher education, the University of Tartu and Tallinn University from a values education aspect; inquired about the values awareness of programme managers, lecturers and students, and tested possibilities of increasing value education competences through practical teacher training. Analysis of teacher training curricula and interviews with programme managers and lecturers revealed that values education and its methods have been described very little or not at all in the curricula; programme managers lack an overview of the representation of the topic of values education in subject areas; the awareness of lecturers on the requirements and possibilities of value education varies greatly. The students who participated in the study found shortcomings in the preparation for value education to be one of the most important factors hindering successful development of attitudes towards values in schools.

Based on this, we prepared a new course, Values Education in the School Context in 2010 under the leadership of Olga Schihalejev, Associate Professor of religious education. The theoretical part of the course introduced the main terms, methods and approaches to value education in the curricula of general education institutions. The practical part involved hands-on teacher training: students compiled portfolios of values education that included examples of values expressed in the school culture and possible discrepancies between declared and lived values. In addition, they had to describe how value education was communicated in lessons and which value dilemmas were being used. Values education was analysed from three aspects: first, noticing, formulating, and clarifying values, second, discussing them, and third, implementing them. We wrote recommendations to the educators of future teachers based on our analysis of curricula and the courses tested out in schools. Values education has now become a recurring topic in many teacher training subjects. At the same time, teacher training curricula might make more room for covering topics of values education and providing future teachers with the necessary skills.

However, teachers already working in schools must also improve their competence in values education. Since there was a dire need for it, we created a further training programme on values education in 2011/2012. 40 persons who had been working as psychologists, counsellors or trainers were accepted into the programme through a competition. In the course of two semesters, 25 of them underwent an extensive interdisciplinary programme that provided both (1) theoretical knowledge on the methods of values education and assessing values development in school, and (2) practical methods of values education and methodologies for analysing the school culture. Graduates of the further training course concluded a contract with the Centre for Ethics to become trainers. As partners of the Centre for Ethics they have been carrying out trainings and consultations on values education in schools and preschools and advising schools and preschools on values education activities since fall of 2012.

In order to help the teachers understand that values are not merely abstract objects of discussion but rather entities that form the basis of their own everyday activities and choices, the Centre for Ethics at Tartu University in cooperation with Implement Inscape, prepared a values game for teachers that is being successfully implemented in values education training courses for schools. The game’s format follows the principle of board games, making the training courses more exciting. In the game, groups of five to six people solve real-life example cases presenting conflicts of values that have been collected with the help of the teachers. After reaching a consensus on a common solution, the players are provided feedback on the values underlying their selection. The values game helps teachers to understand their own and their peers’ values, teaches them to consider values based on certain situations, how to give reasons for the values they selected, how to listen to the opinions of others, and reach a consensus through discussions. The values game for students that teachers can use to initiate discussions on values during homeroom or lessons was finished in 2014.[9]

Given that schools and preschools have great interest in and need for finding out how effective their efforts of value education are, methodological guidance material Analysis of Values Development – Why and How? to support the analysis of values development in schools was developed under the guidance of Professor Halliki Harro-Loit. In this process, we came to the realisation that actual changes are only possible if participants in a school received help in developing their ability of self-analysis and reflection and when they start noticing gaps between their declared and lived values, recognising the patterns preventing the achievement of set goals. As with students, schools also need feedback helping them to understand where they are in their development and what needs to be done for improvement.

In the fifth value education conference The Yardstick of a Good School that took place in 2012, we called attention to the fact that the ‘goodness’ of a school cannot only be measured based on learning outcomes and that we must also evaluate to what extent a school accomplishes the goals provided in its curriculum, i.e. helping students to grow up into creative diverse individuals who can fully apply themselves in various roles in their family, at work and in public life. To do so, a school must provide students with an age-appropriate and safe study environment that has a positive impact and stimulates their development. This environment should foster the students’ desire to learn, their skills in learning, self-reflection, and critical thinking; their knowledge and values. A school’s quality, its goodness is characterised by the extent to which it allows students to realise their interests, inclinations and abilities and find the best options for their further education and profession. We found that, in addition to study results, the learning process, physical environment, management, school culture, and cooperation of the school with various parties should also be considered when evaluating how good a school is. Our goal was not to create an alternative ranking of schools (in addition to the one based on state examination results) but to find a system of evaluation or rather provision of feedback that would support the development of a school as a whole and motivate the school to improve.

Knowing their ranking based on examination results does not inspire schools to become better. Just like getting a bad grade may demotivate a student to learn and a student with great grades may become lazy, schools that drop to the bottom of the list may stop believing in themselves and schools that constantly rank the highest may be tempted to rest on their laurels. It is important that every school wants to grow, analyse their strengths and weaknesses, and find its prerequisites for development. In developing the good school model, we have realised that the most important aspect is increasing a schools’ ability to evaluate the main aspects of their activity (management, learning and education work, school environment, and cooperation between different parties). We help schools to achieve adequate self-evaluation and plan specific development activities through relevant training courses, providing feedback to submissions to competitions, and support from critical friends.[10]

In 2008, we started organising two-day value education conferences in Tartu. Every year, we explore another country’s experience with value education. With the support of embassies and cultural institutions, we have had guests from Australia, the Great Britain, Canada, Norway, Finland, Scotland, Denmark, and the USA. Although our foreign partners have greatly inspired us, we have not been able to simply adopt a value education model that has been developed elsewhere. Estonia has learned from the global experience but tried to find its own way. We can now say that we have invented the Estonian model of value education that has been adopted in our schools and also sparked interest in international partners.

Based on the latest data of the World Values Survey, Estonia has undergone significant development regarding values related to self-expression / emancipation. Although the development of values related to self-expression is dependent on socio-economic conditions, a lot can be achieved through education. Education increases the autonomy and enterprising spirit of learners; larger number of enterprising people boosts the economy; greater economic prosperity in turn promotes wider acceptance of values of self-expression in the society.

In promoting values in the education system and the society, we must not forget our goal of achieving a coherent, safe, peaceful, enterprising, open, and democratic Estonia that preserves its natural environment and preserves and develops the language and cultural heritage of our ancestors but also bravely faces the future. In 2018, Estonia started preparing its long-term strategic plan until 2035. The Values and Responsibility working group led by the Centre for Ethics at Tartu University formulated the future vision for education that is mainly based on lifelong learning and flexible learning.[11] Lifelong learning takes place throughout a person’s life in various learning environments. The future education landscape should be open with no barriers between formal, non-formal and informal education. On the one hand, flexible education must rely on the abilities and interests of each learner and on the other, on the needs of the labour market. In the future, all levels of education will focus more on transferable skills. Due to the ever-expanding amount of available data, more emphasis is placed on skills of finding information, its critical evaluation, and processing and interpreting data. Learners have more freedom to put together their own study plan, select learning content, strategies, and methods. More focus will be on developing independent learners who are ready to take on more responsibility in addition to their increased freedom. An important part of the learning process is providing conscious and systemic feedback between all the parties of the learning process. Grading will transition from checking knowledge to demonstrating competences. Future teachers are learning professionals – active learners who are consistently improving themselves. Teachers are conscious value educators who realise that they influence the learners’ values with their example, attitude towards learning, the learning methods they use, how they provide feedback to learning and behaviour, and how they communicate with learners. Our goal is that by 2035, the management of all educational institutions is values-based, and the head of each educational institution helps to design an organisational culture where all the parties to an educational institution (teachers, learners, support staff, parents) are aware of their responsibility and cooperate to reach common goals.

What have we achieved?

Currently, the transition from a cramming-based to a values-based school has been accepted at least on the discursive level. We believe that our work with schools and preschools has been successful, as the teachers understand their responsibility as value educators and are ever more interested and prepared to become conscious value educators. The increased interest in value education training courses, conferences, collections, games, and participation in the competitions and recognition programme show that schools find value education important.

One of the most important results of implementing values-based education and the values development programme is that learners – whether they are a student, teacher, head of school or preschool, educational institution as a whole, owner of the institution, or parent – have an environment where they can discuss important values, give meaning to them with other members of their school or preschool, and implement them and receive formative feedback and feedforward. As a result of values development that involves the entire school, the target groups – teachers, support specialists, heads of school or preschool, owners of the institution, parents, educators in non-formal education – realise the importance of supporting the formation of values early on and they develop skills to do that. Acknowledging the role of a value educator or conscious values development in an organisation help to raise important questions related to values in the organisational culture and learning and education activities, keep the discussion on value education going, solve dilemmas, and raise even more complex questions or create tasks that shape the personal values of school and preschool members or parties related to them.

We still have a lot of work to do to increase the professionalism and competence of teachers, heads of schools, and support specialists in value education. We also find educating parents and owners of institutions and involving them in value education important. Parents and owners of schools can be an equal partner to educational institutions in making choices based on values and evidence, providing feedback to members of the community, and supporting them.

References

[1] Lennart Meri My Political Testament, compilers T. Hiio and M. Meri. Tallinn: Ilmamaa 2007, p 190.

[2] https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp

[3] A good overview of discussions over values in the society can be found in the collections of the Centre for Ethics, University of Tartu, Contemplating Estonia - Upholding Common Values compilers M. Sutrop and T. Pisuke (Tartu: EKSA, 2008) and Estonia AND Nordic Countries – Estonia AS a Nordic Country? (Tartu: EKSA, 2017).

[4] Based on the essays sent to the essay contest In Which Estonia Do I Want To Live? (Tartu: EKSA, 2007).

[5] https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/129082014020?leiaKehtiv

[6] https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/129082014021?leiaKehtiv

[7] https://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/strateegia2020.pdf

[9] Read more about the games from the article by Mari-Liis Nummert in the same collection.

[10] Read more about critical friends and the recognition programme from the article by Helen Hirsnik and Nele Punnar in the same collection.

[11] “Ekspertühmade tulevikuvisioonid ja ettepanekud Eesti haridus-, teadus-, noorte- ja keelevaldkonna arendamiseks aastatel 2021-2035”. (Visions for the Future and Proposals from Expert Groups to Develop the Education, Research, Youth and Language Fields in Estonia in 2021–2035) The Ministry of Education and Research 2019

Nele Punnar, project manager of the Good School and Good Preschool programme

Helen Hirsnik, values development consultant for schools and kindergartens

Values and value-based choices play a special role in education. The Estonian national curriculum provides the core values of education. In addition, the activities of each educational institution are value-based. However, how do we know if we actually apply the values we have agreed on in our everyday lives? In other words, do the declared and actual values coincide?

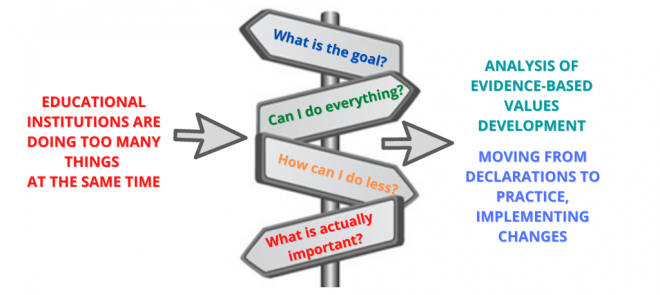

More than a decade of experiences of the Centre for Ethics confirms that values development in educational institutions is a constant circular process of values clarification: agreeing on the most important values, noticing lived i.e. actual values, forming practices supporting certain values based on self-analysis, critical analyses of these practices, and rewording the values, if necessary. (Harro-Loit, 2020)

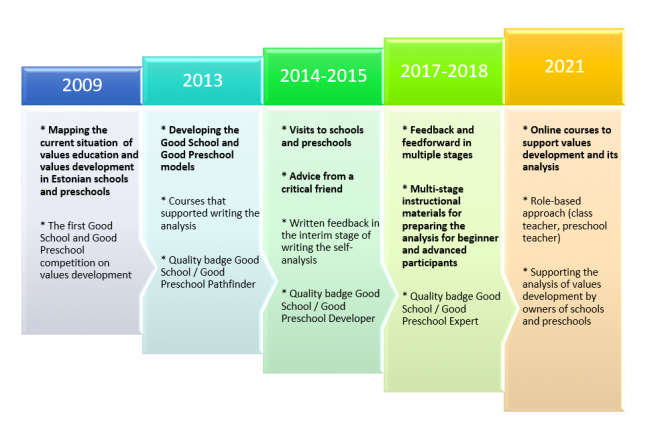

Among other things, the analysis of values development provides answers to the questions which activities are important and why, which activities do not serve their purpose, what needs changing, and what could be cast aside. In addition, the self-analysis focusing on the question of which values are most commonly practised every day helps to detect unimportant and time-consuming activities.

| The self-analyses highlighted the workload of each individual. (Erli Aasamets, head of school*). |

Values development is a constant and time-consuming process both in the education system and on the level of educational institutions. It is a learning opportunity for all participants. Through its Values Development Programme, the Centre for Ethics has been supporting schools and preschools for nearly 12 years. Every year, educational institutions can participate in the Good School and Good Preschool recognition programme voluntarily and free of charge and apply for a quality badge. The desire of educational institutions themselves to analyse and give meaning to their actions – set new goals, realise what could be done better, and plan new activities – is important.

The recognition programmes Good School as Values-based School and Good Preschool as Values-based Preschool have been developed in constant symbiosis: both the Centre for Ethics as an organiser, provider of feedback and supporter, and the schools and preschools that participated in the programme have learned how to best create values-based learning environments.

The Good School and Good Preschool models have been developed to support the self-analysis of educational institutions. In the beginning, the schools and preschools that participated in the programme received feedback in one stage, whereas now we are providing feedback and feedforward in multiple stages. Critical friends from the Centre for Ethics ask questions based on an educational institution’s first version of the self-analysis to support a deeper dive into the topics.

Educational institutions feel honoured to participate in the recognition programme. In 2009, we started with supporting the self-analysis of six schools and two preschools. Now, for the first time in 2020, we found ourselves in a situation where all those who were interested (63 educational institutions) could not get a place in the recognition programme, even though applying for the programme took place in the high-stress remote learning period caused by Covid-19. Over the years, 84 schools and 102 preschools, i.e. nearly 16% of all schools and 21% of preschools have undergone the recognition programme. The number of participants in the recognition programme has been growing for several years which is why we have created online courses that support the self-analysis.

Below, we will provide an overview of the nature of and main changes to the recognition programme that we have made based on the needs and challenges of educational institutions in the course of evidence-based self-analysis. As was mentioned, this has been a symbiotic learning experience, showing that schools and preschools are able to conduct evidence-based self-analysis. Furthermore, we have seen the positive changes that result in schools and kindergartens undergoing the programme.

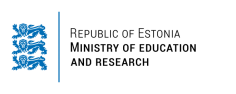

Figure 1. Developments in the Good School and Good Preschool recognition programme in 2009–2021. Composed by Nele Punnar.

The 2021 goals for the recognition programme are as follows:

- Developing the competence of values development and evidence-based self-analysis capacity of schools and preschools;

- Supporting informed choices and planning of development activities by schools and preschools;

- Collecting and distributing good practices through the cooperation network;

- Acknowledging the good practices of schools and preschools.

How did we start?

In 2009, the Centre for Ethics created a competition for schools and preschools that aimed to promote the development of a comprehensive values education programme in educational institutions. Ten years later, we changed the name of the competition: “competition” no longer reflected the content of the analysis process nor the aims of the new learning approach and “recognition programme” seemed more appropriate.

The first self-analyses were more descriptive and revealed that educational institutions were overburdened with activities that had not been thought through. Four important questions (see the figure below) were highlighted that have enabled us to move towards an evidence-based values analysis.

Figure 2. The learning journey of educational institutions and the Centre for Ethics in 2009–2021. Composed by Nele Punnar.

Why is the Good School and Good Preschool model necessary?

After we started the competitions, it soon became clear that schools and preschools needed study materials that supported their self-analysis for developing values based school culture. Simultaneously, we were also looking for criteria that would allow evaluating how “good” an educational institution is. This is why the Centre for Ethics brought together experts in 2012–2013 to develop the Good School and Good Preschool model. The participants were heads of schools, teachers, support specialists, students, parents, researchers, in-service trainers, and employees from the general education and external evaluation department of the Ministry of Education and Research. The most important fields of school life were revealed in the course of discussions and group sessions: learning and education, the school environment, leadership, cooperation, and good relationships. The most important fields of the Good preschool model were regarded learning and education and evaluating a child’s development, an environment that supports growth and development, leadership, cooperation, and good relationships. All these fields are interrelated and form the base for a values-based school or kindergarten (Sutrop, 2017)

Both the Good School and Good Preschool models have been developed further over the years. Introducing the Good School and Good Preschool model has helped to bring attention to the common principles of school and preschool life and the centre of the analyses shifted from values education to values development. Schools and preschools that have analysed their activities under the model have said in their feedback that it is a valuable tool that draws attention to both strengths and weaknesses, thus promoting continuous development. The fact that the areas of the model overlap with areas of the internal evaluation report also motivates the schools and preschools to use the model. Educational institutions submit regular internal evaluation reports according to an agreed procedure. (Sutrop, 2017)

| As we started writing the tasks of the Good School Programme and analyse the aspects that were provided, it made us think how far we wanted to go, how fast, and why. Actually, the Good School aspects provided by the model helped us to clarify the needs and possible perspective of the school. (Erli Aasamets, head of school) |

Who are the Critical Friends?

In launching the Critical Friends Programme, we were inspired by the QiSS (Quality in Study Support and Extended Services) system in Great Britain that focuses on supporting self-analysis in schools with the help of a Critical Friend.

Critical Friends are values development consultants of the Centre for Ethics who have undergone the values development training programme in 2011/2012 and continue to participate in annual development seminars for self-development as Critical Friends. A Critical Friend helps a school or preschool to ascertain and formulate the strengths of their organisation as a whole and draw attention to possible opportunities for development. Critical Friends provide honest, supportive, and constructive criticism and encourages the institution to take even small steps to create an environment that is good and supports learning for all the members of a school or preschool.

Since 2013, Critical Friends have also been providing feedback to the self-analyses submitted in recognition programme by schools and preschools.

| A Critical Friend noticed that our students did not receive enough written feedback, not as grades to their work, but as written feedback in our praise and reprimand system. We set it as a goal in our development plan and have now realised that it still does not function properly. I would now like to know if this is because the teachers lack time or sufficient knowledge /.../. One aspect is knowing the declared values of our school, another aspect is whether the activities that in our mind reflect our values actually do that. This is where a Critical Friend can help. (Anna-Liisa Blaubrük, the head of education quality*) |

How do we support self-analysis?

In our self-analysis seminars for schools and preschools, we focus on topics that support writing, for example setting goals or selecting appropriate data collection methods for Good School or Good Preschool development.

However, the main proportion of the recognition programme relies on personal feedback given to each school and kindergarten. Feedback plays a key role in developing self-analysis capacity. Schools and kindergartens are provided with both written and in-person feedback personalised to their needs during the self-analysis process.

The Critical Friends from the Centre for Ethics have visited nearly a couple hundred schools and preschools in Estonia. The main goal of these visits is to meet with the school and preschool teams in their everyday environment, listen, how and what they talk about their activities and be a fly on the wall in classrooms and hallways to see how relationships between these walls function. Even walking through the front door and having initial contact with the members of a school or preschool speaks for itself. These tiniest signs – how guests are greeted, how people communicate with each other, what kind of an atmosphere the head of school or preschool creates with their presence, the facial expressions of children walking the hallways – indicate values that prevail in schools or kindergartens, whether intentionally or unintentionally.

Often, people are worried about how to prepare their school or preschool for a visit by a Critical Friend. Still, the educational institutions are slightly alarmed that someone is coming to “check up” on them. We have always explained that the role of a Critical Friend is not to check them. We try to help a school or preschool find an answer to the question of to what extent and how everyday practices – communication, agreements, decisions, and rules – support their organisational values.

In the course of these visits, we discuss the goals, results and impacts of these activities with the team. What evidence is there that the values are followed and how is it interpreted? In the course of the discussion, we always ask, whether all the activities are equally important. What is the most important aspect for reaching the desired results and what should be done for this?

The schools and preschools have confirmed that for them, the biggest value of the recognition programme lies in the meaningful eye-to-eye discussions, an outsider’s view of their environment, and shedding light on the so-called dark corners. They say that it is encouraging to have someone show interest in what they do without judging what is right and what is wrong. Often, the schools and preschools do not even realise the positive things that they are already doing, and which everyday practices are related to their goal. It is good to get confirmation for this as well.

The school and preschool visits are also informative for the critical friends and complement the understanding provided by self-analyses.

Figure 3. The stages of self-analysis in the Good School recognition programme. Composed by Õnne Allaje and Nele Punnar.

Providing individual feedback in multiple stages (written feedback and field-visit) have enabled us to transition to providing feedforward to each school and kindergarten. This is a fundamental change that supports educational institutions as learning organisations and is in line with the new learning approach.

| When we started writing the analysis, it was very difficult to decide, what to write and what not to write about. The Centre for Ethics helped us choose what to include, what to leave out, and what would also interest readers outside the preschool. Writing the analysis also showed areas that we should especially focus on in the future. (Margit Toomlaid, head of preschool*) |

How do we recognise educational institutions?

The schools and kindergartens participating in the recognition programme are awarded yearly for their efforts. We have developed a multi-stage recognition system inspired by QiSS for schools and preschools that conduct values-based analyses of their activities.

- First-stage badge: Good School / Preschool Pathfinder (in 2009–2020, we have awarded the pathfinder title 76 times to schools and 75 times to preschools).

- Second, advanced-stage badge: Good School / Preschool Promoter (in 2009–2020, we have awarded the promoter title 44 times to schools and 27 times to preschools).

- Third-stage badge: Good School / Preschool Expert (currently, this has been awarded twice two schools and once to a preschool).

Badges have been added as educational institutions have become more capable of self-analysis. The Expert badge was added recently. A badge is awarded for three years and after that an educational institution must renew it by participating in the recognition programme and writing a new self-analysis.

In addition to the badge, the Centre for Ethics has also given out the travelling trophy with titles Preschool of Value (currently to 17 preschools) and School of Value (currently to 17 schools) at our annual value education conference. These recognitions have been awarded to schools and kindergartens since 2009.

The values development side of the self-analysis that is based on the Good School or Preschool model is considered awarding the travelling trophy: the process of agreeing on values, originating from values both in learning activities and the organisational culture, child-centred approach, systematic nature of the analysis, involvement of all parties, analysis of development needs, and consistency of development activities. Every year, the school and preschool that won the value education travelling trophy the previous year hands it over to the new winner. They are reminded by the highest title of value education by a tree and diploma that they receive with the trophy.

The Values Education Award. Photo: Centre for Ethics, University of Tartu

|

Things started to become clearer in the third year when we began to think about what to do with the weaknesses in our school life and how to make good things even better. The fourth year of writing was already fun. We received the School of Value title and thought, “Now that we have the title, what should we do next? And we assembled the ideas for the next self-analysis in just one week! In that period, the saying “Sometimes information may be hard to face” was introduced in our institution. Then we got the idea to structure our work the opposite way. Instead of writing our success story, we wrote down a problem we wanted to solve. What brought this problem to light, how do we notice it? (Erli Aasamets, head of school*) |

How do we communicate the good practices of schools and preschools?

The participants of the recognition programme have been ensured that their self-analyses are not shown to third persons. This practise has encouraged them to be honest and also own up to mistakes in preparing the analyses. It should be noted that over the past ten or so years, in addition to increasing their self-analysis capacity, educational institutions have also become more confident, and they no longer find anonymity to be the most important factor in the writing process.

Upon receiving consent from schools and preschools, we have published some exemplary self-analyses in the Ethics in Estonia portal to enable other educational institutions also examine the possibilities of values-development analysis and various good practices. To achieve this, the Centre for Ethics organises information days on good practices where schools and preschools that have participated in the recognition programme are invited to share their experience with values-development analysis. As of 2021, we are developing an online database where we can introduce the schools and preschools included in the network to each other and highlight their best practices and experiences.

How do we develop the Good School and Good Preschool models?

The Good School and Good Preschool model are continuously developing alongside with the yearly recognition programme. Reading the self-analyses and the content analysis prepared on the basis of the self-analyses (Parder, Hirsnik, 2020) have revealed that next, educational institutions require a role-based approach to values development. This means that the responsibility and opportunities related to values education of the bearer of each role (heads of schools/preschools, support specialists, other staff, children, parents, and the community) is viewed separately. We have started off with three roles – head of an educational institution, class teacher, and preschool teacher.

In 2020, we invited the heads of educational institutions to have a deeper discussion about values development compared to the past. We offered them the chance to prepare a self-analysis supported by feedback that focuses on the role, identity, values, choices on values, autonomy, and sharing and distribution of responsibility of the head of an educational institution. The process of writing the self-analysis along with providing feedback also gave rise to questions that had caused problems in the past. (Harro-Loit, Punnar, Hirsnik, 2020)

We continue to work with heads of educational institutions and offer them the opportunity to analyse the connection between the values of the head of school and the school itself. By using self-analysis, joint discussion seminars, and literature, we soon hope to develop the Good Head of an Educational Institution model as well as the Good Class Teacher and Good Preschool Teacher models.

How do we maintain the quality of the recognition programme with an ever-growing number of participants?

The recognition programme has undergone several significant changes. Based on the feedback from participants, interest in the programme is mainly large thanks to individual support and feedback that is also the most resource-intensive part of the recognition programme.

In 2021, the preparatory activities of the programme have largely been moved online. We have created online courses that support preparing the self-analysis. The first part enables participants to individually develop their knowledge about values and values-development. The second part of the online course supports team analysis of values-development in schools and preschools with theoretical knowledge and practical exercises that help to find and formulate the focus, goal, and research questions of the analysis. By doing so, we help to support the institutions that are beginning their analysis journey with constructive feedback already in the first stages, helping them to take a deeper dive into the analysis.

The issue we are facing is the small number of schools and preschools that have received the expert badge: as from 2017, only two schools and one preschool have reached the expert level. How do we help the recipients of the promoter badge to advance further? One possible solution that we see is again providing online support related to their topic, supporting analysis with guiding questions, and trainings focused on collection and analysis of evidence-based data.

2021 is a breakthrough year for the recognition programme. Although the Centre for Ethics is reaching more institutions (244 people participated in the first online course alone), does the analysis capacity increase faster than before? This is an important question: the values-development analysis is a tool that helps educational institutions to make values-based decisions in tough times.

| Self-analysis is not a list and description of activities, but rather a search for the connection between cause and effect. It was and still is quite difficult. (Margit Toomlaid, head of preschool*) |

References

Harro-Loit, H. (2020). Eneseanalüüsi käsiraamat. [Self-analysis handbook for schools and kindergartens] Visited at: https://eetika.ee/et/sisu/eneseanaluusi-kasiraamat-haridusasutustele-20…

Harro-Loit, H., Punnar, N., Hirsnik, H. (2020). Koolide ja koolipidajate väärtusvalikutest. Ülevaade haridussüsteemi välishindamisest 2019/2020. õppeaastal [Values-based choices of schools and school owners. External Evaluation Review for Estonian Basic schools 2019/2020] (pp 139–140). The Ministry of Education and Research: Tartu.

Parder, M., Hirsnik, H. (2020). Väärtuskasvatust toetavad tegevused ja nende enesehinnanguline tulemuslikkus Eesti üldhariduskoolide näitel. [Practices supporting values education and its assessment in Estonian schools] Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri, 8(2), pp 245–271.

Sutrop, M. (2017). Sissejuhatuseks. Hea Kooli Mudelist. [Introduction. About the Good School Model] M. Sutrop, H. Toming, & T. Kõnnussaar (Eds.), Hea kooli käsiraamat [The Good School Handbook] (p 15). Estonian Language Foundation: Tartu.

See also:

*Quotes from experts illustrating the article:

Erli Aasamets is the head of the Kilingi-Nõmme Secondary School. In 2018, the Kilingi-Nõmme Secondary School received the School of Values Education Award and in 2019 and 2020, the Good School Expert badge. The Kilingi-Nõmme Secondary School has been acknowledged for effective work in promoting the values-based school.

Anna-Liisa Blaubrük is the head of education quality at the Tartu Kristjan Jaak Peterson Secondary School. In 2016, the Tartu Kristjan Jaak Peterson Secondary School received the School of Values Education Award and in 2017 and 2020, the Good School Expert badge. The school has been acknowledged for systematically developing feedback culture and promoting the values-based school.

Margit Toomlaid is the head of the Rannamõisa Preschool. In 2014, the Rannamõisa Preschool received the Preschool of Values Education Award and in 2017, the Good Preschool Expert badge. The preschool has been acknowledged for valuing and creating an environment for children that supports autonomous decision-making.

Header photo: Centre for Ethics

Mari-Liis Nummert, project manager of the Good School and Good Preschool programme

In our everyday lives we choose between different values, often without even realising it. We often also do not give reason to these choices, which is why the underlying motives may not be clear to other people. However, students, teachers, heads of schools, as well as parents often face conflicts of different values, such as loyalty (to a friend) and honesty (the obligation to tell the truth). How we act in the case of conflicting values and what decisions we make often depend on the person’s ability to differentiate and understand their values. The values games developed by the Centre for Ethics of the University of Tartu aim to give a tool to the different actors in schools to help them discuss upon and give meaning to various situations they might face.

Over the years, the Centre for Ethics and its partners have developed three values games that school family members can use for values discussions:

- Values Game for teachers (2010)

- Discovering Values for students (2012)

- Estonians’ 100 Choices. Discussion Game about Values for the whole family (2020)

What makes the values games special?

Many educators understand the need for values discussions in the school family – either in the classroom, with the parents or among staff members, but admit difficulties initiating or leading the conversations: how to create willingness for a discussion on values and conduct the discussion in a sensitive way without it coming off as lecturing and moralising?

All values games create a safe space for values discussions. Value discussions are facilitated in a gamey atmosphere and revolve around situations participants might face in their everyday life. With each situation, players make values-based choices themselves and with others, promoting the thought and discussion process. A few choices are presented to a participant for each situation and there are no so-called ideal choices: just like in real life, each one has some downsides. In the course of the game, the player decides which one seems more acceptable or least adverse to them. The game makes talking about serious subjects simple and fun – personal, professional or shared values are made visible without any added pressure.

Methodological foundations of the values games

The values games are based on the values clarification method, a value education approach originating from the United States of America in the 1960s. The values clarification method draws on the humanistic ideal that attaches importance to independence and freedom of choice. Various methods are used for values clarification that guide participants to make choices among alternative options, express their values and reflect critically upon their opinions.

Often, the values we agree upon in school, at home or in the society tend to be too general and do not account for everyday situations. The different values and roles are constantly colliding in real life: opinions about what is good or bad are different in school, at home or among friends and everyone has to make sense of these. Even values that we personally find important may be conflicting and their ranking may depend on the context (for example, you may prefer honesty to consideration for others in one situation but find consideration more important in another). In these situations, the knowledge that certain values are important does not offer much help. We must be aware of our values to see the different possibilities and consider the consequences.

Both, the values clarification and value education method centre around the valuing process and the skills required for this – thinking, feeling, choosing, communicating and acting. Each person needs to understand what is important to them, think about the possibilities and consequences, make their own choice, put it into words, and understand the consequences of their choice in everyday life. In the context of value education, “clarification” means having someone clarify their thoughts; gradually realising what their values in a pressure-free environment. In the course of the game, students, teachers, heads of schools or parents get to discover their values in a stress-free environment through discussions, give meaning to the values, and develop them through communication with others. Although discussion and reasoning are important in the game, clarification also focuses on the emotional aspect of valuing, by highlighting motivation, intuition, conscience, and feelings of guilt and empathy.

The method of clarification takes into consideration that the inner deliberation of values and truly accepting them is a decision that is better supported by free discussions rather than moralising. By realising the importance of certain values on our own we are more motivated to act accordingly.

Values games: discovering values playfully

The format of the values games is playful, but educational. The games support the development of self-reflection and discussion skills of players, increase empathy within the group, and develop functional reading skills of the players. The main proportion of the game is made up of case descriptions inspired by the dilemma method and possible options on how one might act. With each situation, participants first choose a solution most suitable for them and justify it to the other players, allowing to view the same situation from different perspectives. Since the purpose of the discussion process is to form personal opinions, wording them and giving reasons, there are no right or wrong answers in the game. The players choose between more and less preferred ways of acting but decide on their own whether the choices are acceptable. Second, the players seek for common ground – which solution would be best in groups opinion? The discussions within the group last until the group has reached consensus or in some cases, have respectfully agreed to disagree on the best course of action. Every round of play concludes with values-based feedback to the given situation and the group picks.

DISCOVERING VALUES

Discovering Values game set. Photo: Centre for Ethics

Discovering Values, a game for students is a methodical tool for discussing values with students. The game helps students to get to know themselves and think why they hold certain values important. The game consists of real-life cases that students may face in their lives. The game can be played during lessons or outside them (during recess, on a trip, etc.), as a whole or in parts. The game is free of charge for schools: each school that participates in the game training of the Centre for Ethics gets a game kit. Currently, more than 350 schools have the student game Discovering Values.

VALUES GAME

The Values Game for teachers game set. Photo: Centre for Ethics

The Values Game for teachers has been created to help teachers understand their role as value educators. The game helps teachers to hold value-related discussions amongst each other about various situations and conflicts of values and reach common understandings or principles to stem from in their everyday lives. The game for teachers consists of descriptions of different cases related to teaching and the options provided to solve them. The trainers from the Centre for Ethics of Tartu University use the game for teachers and the aim of these trainings is to support the development of a school’s values. The game is used both as a tool for clarifying the teachers’ personal and professional values and as a starting point to observe the values of the school.

ESTONIANS’ 100 CHOICES

Estonians' 100 Choices game set. Photo: Centre for Ethics

Estonians’ 100 Choices is a discussion game for the whole family and is meant for a broad audience from teenagers to the elderly. The game aims to promote discussions on values among people and help them better understand themselves, also developing their skills of reasoning. Through the game, the participants can solve the situations presented in the cases in a stress-free environment by discovering what kind of moral reasoning they prefer in their decisions. The cases chosen for the game are common situations in the Estonian culture and are related to the family, community, environment protection, and other similar topics. Stories inspired by well-known works of fiction have been used in addition to real-life situations. The game can be borrowed from the Centre for Ethics library or bought for home use.

Can games like these be created for my country?

Yes! The methodology of the values games is universal – the presented choices on values inspire discussion among people of all ages and walks of life. In addition to the aforementioned games, the Centre for Ethics has also created a values game for doctors and medical professionals. The Centre has successfully used a similar methodology to foster research integrity (Estonian Code of Conduct for Research Integrity), highlight the chosen professional values of and promote value-related discussions among politicians, museum employees, servicemen, ministry employees, researchers, youth workers, and representatives of many other fields. It is important to stress that each game should fit the target groups' needs. Value choices are often culture-specific which is why the chosen cases should rely on real-life stories of the target audience. This means it is crucial to consider the peculiarities, needs and conditions of each target group when developing a new game. The game experts from the Centre for Ethics are prepared to advise game enthusiasts from other countries.

Values games. Photo: Centre for Ethics

In addition

Step-by-step instructions and examples of cases

A table of comparison of the games

Header photo: Centre for Ethics

Mari-Liis Nummert, project manager of the Good School and Good Preschool programme

In more than a decade, the Centre for Ethics of the Tartu University has organised value education conferences aimed at giving heads of schools, teachers, support staff, and other people engaged with the field of education the chance to discuss the main topics of value education, give meaning to their work, find new ideas and inspiration, and explore the experiences of other countries, This is the largest conference of its kind, bringing together more than 200 educators across Estonia every year. Over the years, focus has been placed on the long-term goals of education, the role of values in education, as well as issues related to the Good School Model such as values-based feedback and feedforward, assessing the values development in a school, or noticing and solving dilemmas on values faced in a school.

The conference topics are based on discussions in the society and education – the conference team closely monitors what is happening in the society and listens to the opinions of people from schools and partners in the field of education. Inspired by these discussions, a programme that introduces both Estonian and international experiences and makes it possible to learn practical tips is put together.

Over the past ten years, we have explored the experiences in value education of the USA, Finland, Denmark, Scotland, Norway, Canada, and England in addition experiences from our own practitioners and experts. For example, we have familiarised ourselves with QiSS (Quality in Study Support and Extended Services) and received good tips from experts of research or practice centres that coordinate programmes of character education in other countries (Center for Character and Citizenship, Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, Values-based Education International, Association for Character Education).

The value education conferences have also placed emphasis on the practical aspect by creating a platform for discussions and solving everyday issues (i.e., how to establish good relationships in a school, how to prevent bullying or support entrepreneurship), but also exploring methods of active learning and finding out how to apply them. The target group of the conferences includes anyone interested in topics related to education – teachers, managements of schools and preschools, support specialists, education officials, as well as parents and students. The conference materials, i.e., summaries of speeches and video recordings, will be made available to anyone interested as study materials after the conferences.

Past conferences

(Information on past conferences in Estonian)

02.-03.12.2020 Conference “Equity in Education”

09.12.2019 Conference “Character: practise makes perfect?”

26.09.2019 Conference “Values-Based Education in Kindergarten: All I Need to Know in Life I Learned in Kindergarten”

06.-07.12.2018 Conference „Estonia 2035 – Values-Based View on Education”

21.-22.11.2017 Conference “To Listen and to Speak: Dialogical Communication at School”

09.12.2016 Conference “Dilemmas in School Life”

10.12.2015 Conference “Good School as Values Based School. How to Develop Entrepreneurial Attitudes?”

10.12.2014 Conference “Good School as Values Based School. How to End Bullying in Schools?”

12.12.2013 Conference “Good School. Mirror Mirror on the Wall, Who's the Best of Them All?”

04.12.2012 Conference „The Yardstick of a Good School“

08.-09.12.2011 Conference “The Expectations of the Society and the Changes in the Schools”

02.12.2010 Conference “Evaluating Schools, Assessing Pupils”

03.12.2009 Conference “Student - the Subject or the Object of Value Education?”

03.12.2008 Conference “Values and Value Education: The Choices and Chances of Estonian and Finnish Schools in the 21st century”

Foreign speakers in the value education conferences

Teacher as the Bearer and Mediator of Values, Hannele Niemi (University of Helsinki)

Values in Vocational Education, Seppo Helakorpi (Vocational Teacher Education Unit in Hämeenlinna).

From Dissemination to Dialogue in the Danish School System, Lotte Rahbek Schou (Aarhus University)

Democratic Education and Citizenship Education in Danish Schools, Ove Korsgaard (Aarhus University)

Scottish Experience: “Assessment for Learning” Programme, Ernest Spencer (University of Glasgow)

Children's Well-being and Self-Esteem, Ruth Cigman (University of London)

Self-Evaluation by Students as a Key to Better Student Motivation, Reet Marten-Sehr (Pearson Canada Professional Learning Services).

What Characterises the School which Gives the Pupils a Good Base for Spending a Happy Life?, Godi Keller (Parents’ Acadamy of Norway in the Rudolf Steiner University College in Oslo)

Children’s’ Rights, Professor Suvianna Hakalehto-Wainio (University of Eastern Finland)

Shaping Entrepreneurship, Professor Emeritus Paula Kyrö (Aalto University)

Making Entrepreneurial Skills Count, Tom Ravenscroft (Enabling Entrepreneurship)

How to Lead Values-Based Schools? What Are the Main Challenges?, Neil Hawkes (UK, Values-Based Education International)

Flourishing Feedback: Creating the Conditions for Constructive Criticism, Liz Gulliford, PhD (The Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham)

What Works in Character Education, Melinda Bier, PhD (Center for Character and Citizenship at the University of Missouri-ST. Louis)

Servant Leadership Serves Character Education, Deborah Sanders O'Reilly (Center for Character and Citizenship at the University of Missouri-ST. Louis)

School Educators' Moral Professionalism in Practice, Eija Hanhimäki, PhD (Jyväskylä University)

Teaching Character for Educational Equity – How Can Every Student Flourish Through Character Education?, Gary Lewis (Association for Character Education)

Õnne Allaje, communication specialist

Values education

An open beginning: a selection of recipes to create a multi-cultural kindergarten (2018): This is a practical handbook with helpful studying/teaching methods for helping in preparing kindergartens for receiving children with migration or refugee background and supporting the creation of a culturally and religiously diverse and tolerant study environment.

Analysis of Values Development - Why and How? (2011): Values development is a way to enhance school culture so that everyone would feel better in their school. Analysis of values development helps to clarify the values that are expressed, reproduced, strengthened and denied through everyday’s activities. The book explains how to carry out an efficient analysis of values development in your school.

Feedback. A Handbook for Teachers, Parents and School Leaders (2019): A practical handbook on how to seek, give and receive feedback on various levels, for example, peer-to-peer, supervisor-to-subordinate, teacher-to-student etc.